Mound of the Dead: A ‘Modern City’ with a Population of 40,000 in Pakistan, Where the Residents Went, Nothing Is Known

In the plains of Pakistan’s dusty southern province of Sindh lie some of the most astonishing ruins of an ancient civilization that most of the world has never heard of.

More about Mound of the Dead:

A Glimpse of the Past

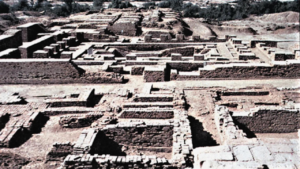

When I explored this ancient city, I couldn’t help but marvel at its history. The warm breeze brought relief from the intense heat as I strolled through a labyrinth of walkways and wells constructed from millions of red bricks. It was as if these bricks held the stories of countless generations, connecting the different neighborhoods that once thrived here.

Amidst the ruins, I came across an ancient round Buddhist dome standing in a decaying state. Below it lay a bathing pool with wide steps, a testimony to the once-vibrant life that characterized this place. However, there were only a few people around, and the city of Larkana, an hour’s drive from the main city, known as Moen Jo Daro, remains today as mere remnants of a thriving civilization.

Moen Jo Daro: The ‘Mound of Men’

Moen Jo Daro, which translates to ‘mound of men’ in Sindhi, was not just another ancient city. 4,500 years ago, it was not only one of the oldest cities in the world, but it was a thriving hub with the most advanced infrastructure of its time. This city was once the heart of the Indus Valley Civilization, also known as the Harappan Civilization, which dominated a vast region from eastern Afghanistan to northwestern India during the Bronze Age.

At its peak, Moen Jo Daro was believed to be home to at least 40,000 people and flourished from 2500 BC to 1700 BC. Irshad Ali Solangi, a local guide and the third generation of his family to work in Moen Jo Daro, explained, “It was an urban center with social, cultural, economic, and religious links with Mesopotamia and Egypt.”

However, unlike ancient cities like Egypt and Mesopotamia, which thrived during the same era, Moen Jo Daro remains relatively obscure on the global stage. The city was mysteriously abandoned and destroyed by 1700 BC, and the reasons for its inhabitants’ migration and their destination remain shrouded in mystery.

Unearthing the Past

Archaeologists first set foot in this area in 1911 after hearing reports of ancient brickworks. Initially, the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) dismissed the significance of the bricks found at the site. It wasn’t until RD Banerjee, an ASI officer, arrived in 1922 and believed he had discovered a buried dome, typical of where Buddhists meditated, that the importance of this place became apparent. This discovery led to extensive excavations, and in 1980, UNESCO designated Moen Jo Daro as a World Heritage Site.

The remains of Moen Jo Daro, particularly those discovered by the British archaeologist Sir John Marshall, provide insights into a level of urban sophistication previously unseen in history. UNESCO hailed Moen Jo Daro as the ‘best-preserved’ ruin of the Indus Valley.

Modern Amenities in an Ancient World

One of the most remarkable features of Moen Jo Daro was its sanitation system, which surpassed that of its contemporaries. While ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia had some drainage and private latrines, these were considered luxuries for the wealthy. In contrast, Moen Jo Daro had a comprehensive system of hidden latrines and covered drains. More than 700 wells, in addition to a system of private baths, were uncovered during excavations. Notably, there was a huge ‘Great Bath,’ measuring 12 meters by 7 meters, for communal use. The city’s advanced sewage system disposes of waste discreetly and efficiently.

“This is a complex and modern system of a city that we would like to live in today,” remarked Uzma Z. Rizvi, an archaeologist and associate professor at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn who has studied Moen Jo Daro extensively.

A Well-Planned City

The people of Moen Jo Daro were not just masters of sanitation and waste disposal. They were urban planners of the highest order. The city featured a grid of meticulously planned, narrow streets intersecting at 90-degree angles. Homes had doorways with thresholds, much like those we find today, marking the transition from outdoors to indoors.

“When you see a threshold, you know someone has thought about what it means to be inside and outside,” said Rizvi.

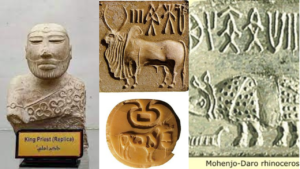

Moen Jo Daro’s residents were not just advanced in their understanding of sanitation; they were masters of mathematics, geometry, and even fashion. The artifacts discovered, including ornate seals, sculptures, jewelry, and pottery, attest to their sophisticated tastes and skills.

However, despite the wealth of information gleaned from these archaeological finds, many mysteries about the lives of Moen Jo Daro’s people remain unsolved.

The Enigma of Moen Jo Daro’s Disappearance

While ancient texts often reveal the secrets of other civilizations, Moen Jo Daro’s script, known as the Indus Valley style of writing, remains undeciphered. It was a pictorial language with over 400 characters, but no one has yet been able to read it.

The city’s decline and ultimate abandonment around 1700 BC also remain a mystery. While climatic factors are believed to have played a role in its destruction, the city did not vanish overnight. The exodus from Moen Jo Daro happened gradually, with certain neighborhoods depopulating over time.

After thousands of years of surviving the elements, Moen Jo Daro faced a new threat in August 2022 when a devastating super flood hit Pakistan. Conservationists and archaeologists like Dr. Asma Ibrahim worked tirelessly to protect the site, diverting excess water from it.

The future of this ancient city relies on a long-term strategy to ensure its preservation. Such a plan will not only benefit archaeology but also the local communities living nearby. The residents of Moen Jo Daro were pioneers of urban planning and sanitation, and their investment in public welfare paid off. For now, this remarkable city stands as a testament to their foresight and advanced civilization, waiting to reveal more of its secrets to future generations.